By Colette Coleman

Following Nat Turner’s rebellion of 1831, legislation to limit black people’s access to education intensified. But enslaved people found ways to learn.

On August 21, 1831, enslaved Virginian Nat Turner led a bloody revolt, which changed the course of American history. The uprising in Southampton County led to the killing of an estimated 55 white people, resulting in execution of some 55 black people and the beating of hundreds of others by white mobs.

While the rebellion only lasted about 24 hours, it prompted a renewed wave of oppressive legislation prohibiting enslaved people’s movement, assembly—and education.

At the same time, abolitionists saw an opening for the argument that the system of slavery was untenable. Lawmakers in Virginia argued over which path to take. A vote to free slaves through gradual emancipation gained support with the state’s leaders. “It was a legitimate debate,” says Patrick Breen, author of The Land Shall Be Deluged in Blood: A New History of the Nat Turner Revolt. It was “not obvious that it wasn’t going to pass.”

Ultimately, however, Virginia and other southern states opted to keep slavery in place and tighten control of African Americans’ lives, including their literacy. In the antebellum South, it’s estimated that only 10 percent of enslaved people were literate. For many enslavers, even this rate was too high. As Clarence Lusane, a professor of political science at Howard University notes, there was a growing belief that “an educated enslaved person was a dangerous person.”

The 1831 revolt confirmed this view, which had been gaining steam for years. Turner was a passionate preacher guided by spiritual visions. His ability to read the Bible allowed him to find stories of divine support for fights against injustice, explains Sarah Roth, professor of history at Meredith College and creator of The Nat Turner Project.

Enslavers and their clergy controlled the Biblical narrative among illiterate enslaved people, but educated black Americans, like Turner, saw past this “sanitized” version, which didn’t call slavery into question.

Abolitionists Agitate Through Written Word

African American literacy wasn’t just problematic to enslavers because of the potential for illuminating Biblical readings. “Anti-literacy laws were written in response to the rise of abolitionism in the north,” says Breen. One of the most threatening abolitionists of the time was black New Englander David Walker. From 1829-1830, he distributed the Appeal, a pamphlet calling for uprisings to end slavery. Black sailors brought Walker’s text, surreptitiously sewn into the seams of clothes, to the South.

There’s no proof that Turner, himself, read the Appeal and was inspired by it, according to Edward Rugemer, a history professor at Yale University. However, there’s “a lot of evidence that abolitionist writings directly influenced” Caribbean uprisings around this time, he notes. If written “abolitionist agitation was shaping the nature of slave resistance” in the islands, American enslavers believed that it could influence enslaved populations stateside.

Adding to such fears was William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist paper, The Liberator, which began publishing on January 1, 1831. Although it was edited by Garrison, who was described as a “radical” white abolitionist. Rugemer argues it was seen mainly as a “black newspaper,” since most of its readers were African Americans. Along with a “few radical whites who believed in antislavery and antiracism.” Southern enslavers saw this paper as another example of outside agitation spread through the written word.

Literacy Threatens Justification of Slavery

Black Americans’ literacy also threatened a major justification of slavery—that black people were “less than human, permanently illiterate and dumb,” Lusane says. “That gets disproven when African Americans were educated and undermine the logic of the system.”

States fighting to hold on to slavery began tightening literacy laws in the early 1830s. In April 1831, Virginia declared that any meetings to teach free African Americans to read or write was illegal. New codes also outlawed teaching enslaved people.

Other southern states passed similarly strict anti-literacy laws around this time. In 1833, an Alabama law asserted that “any person or persons who shall attempt to teach any free person of color, or slave, to spell, read, or write, shall upon conviction thereof of the indictment be fined in a sum not less than two hundred and fifty dollars.” (The fine would be the equivalent of about $7,600 in today’s dollars.)

Despite the consequences, many enslaved people continued to learn to read. And numerous enslavers may have supported this. Many enslaved people did “sophisticated work, including management of operations,” which required literacy, explains Rugemer. Barring black Americans from reading and writing wasn’t a practical strategy for anyone.

And it was too late.

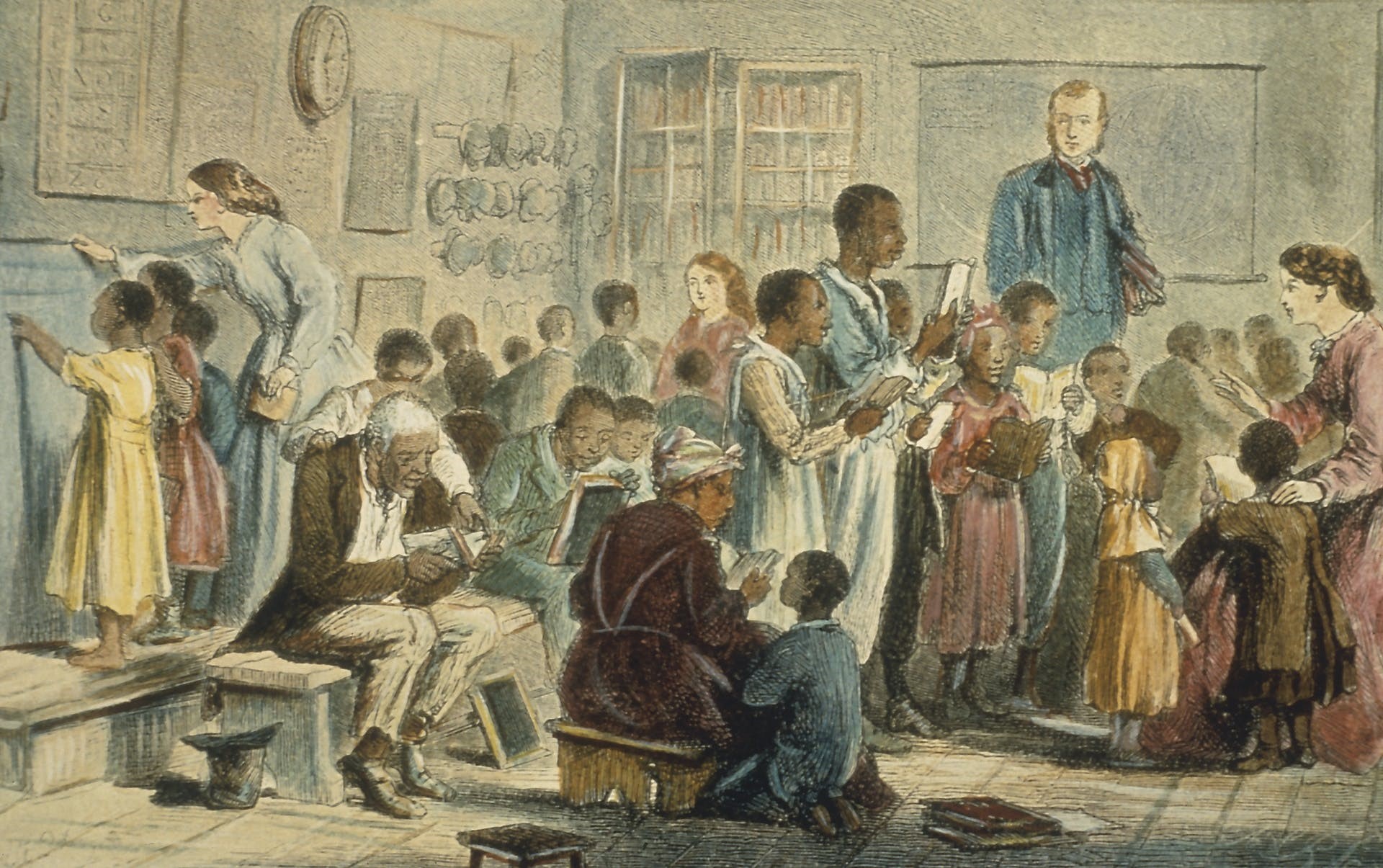

After the Civil War, Schools Spring Up

Antislavery ideas had already spread, largely through the written word. As Roth points out, “Literacy promotes thought and raises consciousness. It helps you to get outside of your own cultural constraints and think about things from a totally different angle.”

The view that slavery was wrong and should be ended was reinforced through written texts. Soon after Turner’s rebellion, in 1862, the Emancipation Proclamation declared that all slaves in the states currently engaged in rebellion against the Union “should be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

When U.S. army units began arriving in Virginia in 1861, members of the freed black community quickly began opening up schools for African Americans, staffed with black teachers, as well as white Northerners. Following the end of the Civil War, literacy rates climbed steadily among black Americans, rising from 20 percent in 1870 to nearly 70 percent by 1910, according to the National Assessment of Adult Literacy.